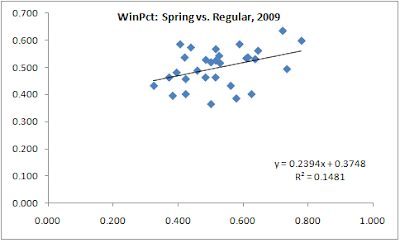

I thought I would take a look at whether spring training records matter or not. Clearly the teams are not playing to win. But, in the extreme, my guess is any MLB roster spring training effort is going to be much better than, say, a high school team's effort. An extreme example, but I was curious if spring records convey any predictive value to what is going to happen in the regular season.

My answer is that they do, a little. Or, better put, they do some seasons. I looked at the latest 8 seasons (2002-09). In 5 of those seasons you had a positive correlation between spring training win percent and regular season. In three years you have very little or slightly negative correlations, but in the other 5 you have reasonably positive correlations.

My answer is that they do, a little. Or, better put, they do some seasons. I looked at the latest 8 seasons (2002-09). In 5 of those seasons you had a positive correlation between spring training win percent and regular season. In three years you have very little or slightly negative correlations, but in the other 5 you have reasonably positive correlations.

So it is never a bad thing to have a good record. At worst it says nothing about your regular season, but other years it says you will probably have a decent season.

The trends in 2007-09 may just be random but it will be interesting to see what happens in 2010.

Another way too look at this is to group teams by their spring records and see what their average winning percentage was for the regular season:

x is the spring winning percentage (x axis) and the vertical is regular season winning percentage. So, if you had a .400 or worse winning percentage in the spring season of 2009, you are the left most column. So there is some correlation. There is wide variation, but still, a relationship. 2009 was a particularly strong correlation (.385). So for all 8 years:

Looks kind of similar to the 2009 numbers. Interesting that the teams that did very poorly (x<.400) generally do better than those that do less poorly (x<.450). I wonder if that is because the teams that know they are going to be bad try a bit harder to win games in spring training because they hope it will translate into some lift in the regular season vs. those that recognize that the games do not matter.

This is not to say that teams should try to win games. This analysis suggests, that even when teams are not trying to win games, but the players are trying to perform well, those outcomes convey a modest amount of information.